Neapolitanism and the quick fall of an Idealized Place.

Long form content ahead, you've been warned.

Growing up in Benevento, just a stone’s throw from Napoli, I always carried the duality of being Italian and being Southern. You’ve likely heard the stereotypes: comical mimicries of Italian accents punctuated with “Pizza! Mafia!”. Sure, I heard most of these while studying abroad- the joys of being an expat in Northern Europe- and on my favorite TV shows, but Northern Italians would say stuff along these lines too, not too long ago1. As a Southerner, I often found these reductive portrayals irksome but expected. After all, being from the South of Italy wasn’t a badge of pride to the world; it was something of an open secret that even other Italians looked down upon. Napoli? It was said to be chaos, dirt, and desperation—fascinating from a distance, perhaps, but hardly a destination for celebration. At least, that’s how it felt back when I was growing up. It wasn’t always like that, it was worse for a while, better for another while, incredible yet another time, and so on.

To give you a partial idea of public perception, these are a few occurrences that shaped it from the 60s onwards. Bear with me.

1960s: Chaos and Cinema

Starting with Post-WWI, when Napoli was synonymous with poverty, overcrowded neighborhoods, and lingering damage from war. The Neapolitan slums became infamous, reflecting broader issues of Southern underdevelopment in Italy. The Italian government's economic focus on industrializing the North left the South struggling, reinforcing stereotypes of the Mezzogiorno as backward and chaotic.

At the same time, the rise of Italian cinema brought Napoli to the forefront, particularly with Vittorio De Sica’s Gold of Naples (1954), which depicted the city’s charm and resilience despite its hardships. This image lingered into the '60s, giving glimpses of the city's artistic soul.

Napoli’s culinary and cultural exports (e.g., Neapolitan pizza and music) gained international recognition during this window of time too, sparking a fascination with its traditions.

1970s: Camorra and Funk

The 1970s saw the Camorra growing in power and influence. Raffaele Cutolo, leader of the Nuova Camorra Organizzata (NCO), emerged as a major figure. This period marked the expansion of organized crime into drug trafficking, extortion, and control over public contracts, leading to pervasive corruption and fear in Naples.

This decade saw unemployment rates soaring in southern Italy, particularly in Naples, as the region lagged behind the industrial North. This led to increased poverty, emigration, and a growing sense of disillusionment among locals.

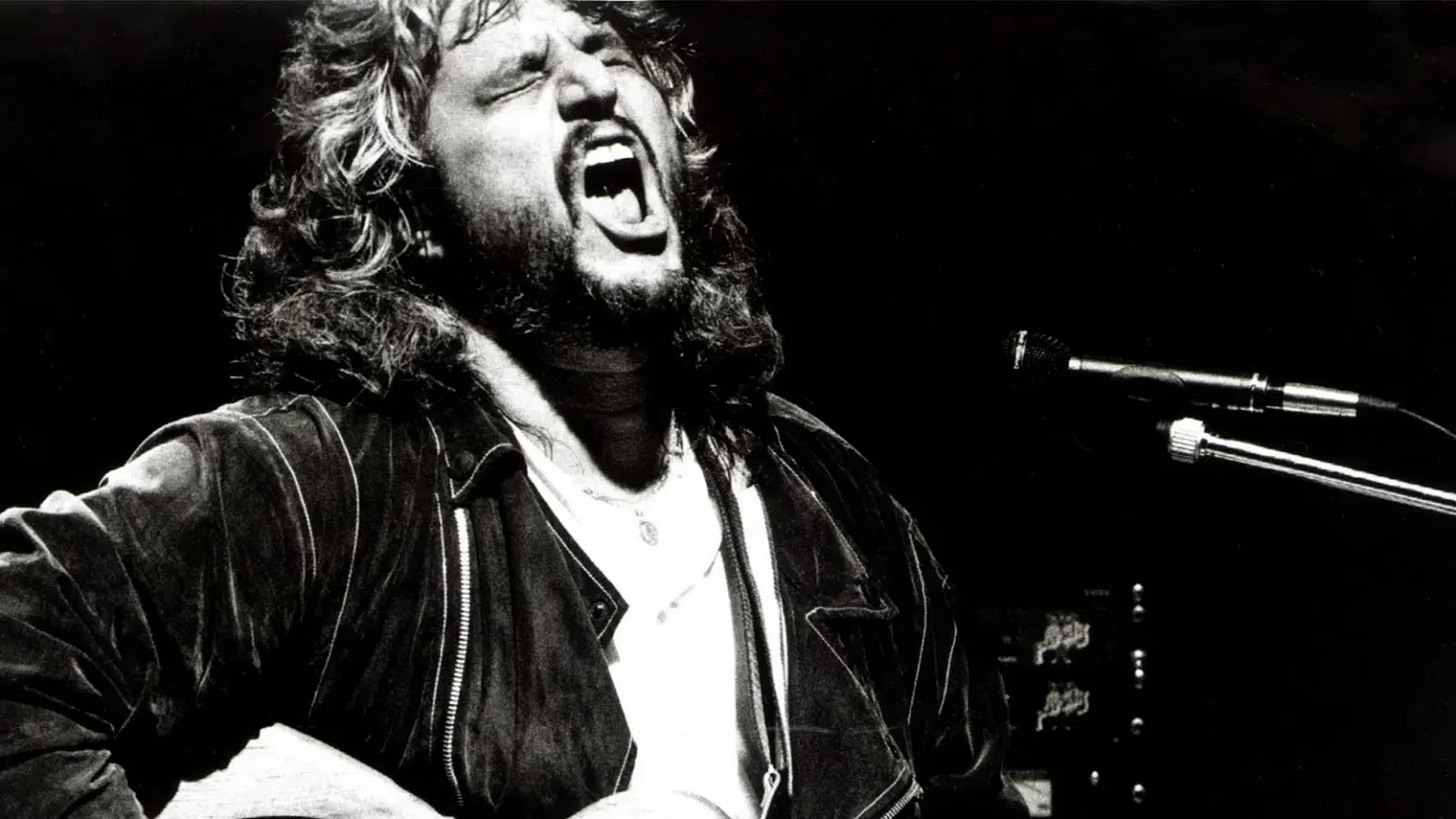

Regardless, the music was riveting. Neapolitan funk and pop culture began to thrive. Artists like Pino Daniele2 emerged as icons of Napoli’s rich musical heritage. His blend of jazz, blues, and traditional Neapolitan sounds reintroduced the city as a hub of creativity.

Napoli also saw a resurgence in the performing arts, with local theaters and festivals celebrating its rich traditions.

1980s: The Maradona Era

The 1980s Irpinia earthquake had a devastating impact on the region, creating widespread economic struggles and solidifying the South’s image as a region mired in misfortune. Another unfortunate occurrence was when my parents met each other while volunteering to help the areas most affected by this tragedy.

Meanwhile, organized crime continued to dominate international headlines, overshadowing the city’s cultural contributions.

The arrival of Diego Maradona in 1984 transformed Napoli’s image globally. With his genius on the field, he led SSC Napoli to two Serie A titles (1987,1990) and a UEFA Cup (1989). Maradona’s success made Neapolitans proud and brought the city international acclaim.

Napoli became a global cultural touchstone as Maradona’s feats connected with its narrative of resilience and defiance.

1990s: Stagnation and Glimpses of Revival

During this decade, the Camorra was marked by widespread violence and territorial disputes in the aftermath of Cutolo’s decline, paving the way for the Casalesi clan's rise to power. Media coverage frequently portrayed Naples as a city gripped by chaos, danger, and lawlessness.

Napoli faced growing environmental challenges, including a garbage disposal crisis that drew international criticism.

Music-wise, we had it all. The iconic British group, Massive Attack, made a track called Karmacoma (The Napoli Trip) ft Almamegretta’s singer Raiz. You have to listen to it if you love trip hop, reggae, dub, rap, and Neapolitan cadence. It’s impossible to name everything that has happened in this space during these years. The group 99 Posse was a national trailblazer: from illegal squats to the MTV mainstage, using Neapolitan dialect on a sound that threads over reggae and hip-hop beats. “Posse” stands for group or militia and it was a musical phenomenon born in tune with the development of squatting movements. The 99 Posse was born in 1991 as an expression of the “Centro Sociale Occupato Autogestito” Officina 99, a squat in Naples. If you want to look up who introduced the Italian language and political militancy to hip-hop, look no further than Onda Rossa Posse. Their album, Rap Poesia della Strada, is from 1990 and perfectly embodies the spirit of that time across the nation. But they’re from Rome, and we must return to Naples. Its streets were electric; the first entities that shaped this energy were the Angels Of Love and United Tribes. These collectives were amongst the first to believe in house music and arranged epic parties with international talents performing in the city. United Tribes took on a more radical approach to the events, which became channels for visions of political noise and punk attitudes. Napoli had lots to say.

In 1994, the movie Il Postino (partially shot in the Campania region) brought worldwide attention to the beauty and poetry of Southern Italy. The movie had 5 nominations at the Oscars (Best Picture, Best Actor in a Leading Role, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score), winning for Best Original Score. Additionally, at the 1996 BAFTA Awards, the film received: Best Film Not in the English Language; Best Direction for Michael Radford; and Best Film Music for Luis Bacalov.

Massimo Troisi was posthumously nominated for Best Actor in a Leading Role and Best Screenplay at the BAFTA Awards. He was an incredible talent who sadly passed away on June 4, 1994, just one day after completing filming for Il Postino.

Napoli’s cultural renaissance persisted during the remaining years of the decade, with continued global interest in Neapolitan music and theater.

2000s: Contrasts and Challenges

The city became emblematic of Italy’s garbage crisis, with streets piled high with trash due to poor waste management. It became a symbol of governmental inefficiency and corruption. The Camorra has its hands in many businesses, so it was central in the illegal disposal of toxic waste all over the Neapolitan hinterland. The Campania region was then called “Terra dei fuochi”, “Land of fires”. The name came from the unlawful disposal procedure, which constituted numerous waste fires that spread dioxin and other polluting gases into the atmosphere. This and the illegal landfills made for a significant increase in the incidence of specific pathologies, mortality from leukemia and other tumors. The expression “Terra dei fuochi” first appeared in 2003, when it was used in the Ecomafia Report of that year, edited by Legambiente.

Crime and poverty remained key talking points in international narratives about Naples.

Roberto Saviano came out in 2006 with the book “Gomorra”. His first work as a writer became a global phenomenon. Nobody had ever spoken about the organization that upheld the Mafia power worldwide, he did just that. “Terra dei fuochi” was used by Saviano in the book, as the title of the eleventh and final chapter. It is worth remembering that at the time, Italy’s President Silvio Berlusconi said that it gave the Mafia too much visibility and damaged the idea foreigners would have of Italy.

Matteo Garrone directed Gomorra, the movie, in 2008. Co-written by Saviano, the movie was a success. “The greatest Mafia movie ever made. Strips every last pretense of romanticism from the ‘Godfather’ saga.” said Stephen Shaeffer, a reporter at the Boston Herald. I mention it so that you see where the criticism was coming from. It’s not palatable, it’s not a hero's journey. It showcases a violent system and the reasons it sticks.

2010s: AUTHENTICITY IS KEY

In the 2010s, Napoli experienced a cultural revival that elevated its global standing as a center of art, music, and gastronomy. However, this renaissance was marred by persistent stereotypes, challenges of gentrification, and environmental and economic struggles. The decade saw Napoli caught between being celebrated for its authenticity and criticized for its perceived chaos and exoticization.

A cultural product of these years was Gomorra, the TV series. It was an international success, but it also started the critiques where the mafioso costume was sewn up on the Neapolitan population as a whole. More than that, it seemed to simplify the dynamics of systemic violence in Gomorra the book, making them human and entertaining. Think back to the critiques that the book received when it launched, positive and negative ones. The passage made here was from a work of reportage to a work of fiction, many people said that in this translation the characters were too human. While it’s easy to understand where the critiques came from, I believe the fallacy lies elsewhere.

In any work of fiction, you have a hero’s journey. In this case, you have multiple heroes on different quests, but they’re not going against “evil”. They are working from within it, in quests dictated by power, which are never completed. There is never a win. Not one that feels like the ultimate one, is just a temporary slot they inhabit before a new threat comes into the picture. Many complaints have been made by people working in the justice system, as to how this work portrays a Mafia that is long gone and that now operates differently. These days it seems more of a silent threat, looming within the institution, and so I’d say that more than making the characters too human, the error might lay in the overtly caricatured dynamics.

There is a scene from “Il sol’ dell’avvenire” by Nanni Moretti, which came out last year, and I want to share just this scene: Giovanni, a famous director in his 70s, has to watch a scene of a shoot-and-kill movie, and this scene feels like a testament to the Gomorra aftermath. Two men are shooting each other, with overtly dramatic tones and interactions. The way it’s staged, epic and cinematic, in Neapolitan dialect, alludes to the spectacle of violence that we currently associate with the Neapolitan series. Far from reality, a parody of itself, but a lucrative one.

Where’s the line between real and fiction? More about this in a few paragraphs.

Music-wise, I’d like to highlight two artists who cemented the Neapolitan sounds in these years: Nu Guinea, now Nu Genea, and Liberato. Both blended traditional Neapolitan elements with modern sounds, reshaping the city’s musical identity for a global audience.

We had the pandemic in 2020 and while the world stopped, pictures of a vibrant place just around the corner emerged. Sunny, loud, full of life. Embodying all that we were missing in our isolation, Napoli came to the forefront on our screens.

2020-NOW

In recent years, Napoli has undergone a peculiar transformation. It has become a fashion darling, an “idealized” backdrop for Instagram photographers and glossy magazines alike. The world now says they love Napoli, but do they? Or do they merely love the images?

As I’ve written above, this city is not well equipped when it comes to being bidimensional, it can be so only if you decontextualize what you see and stop in awe of its beauty.

Think back to the “Vita Lenta” craze, read a few articles about people from other countries who moved to Italy searching for it, and prepare to be shocked- they hate it here. “It’s nothing like the pictures”, who would have thought? A real place, with real complexities?

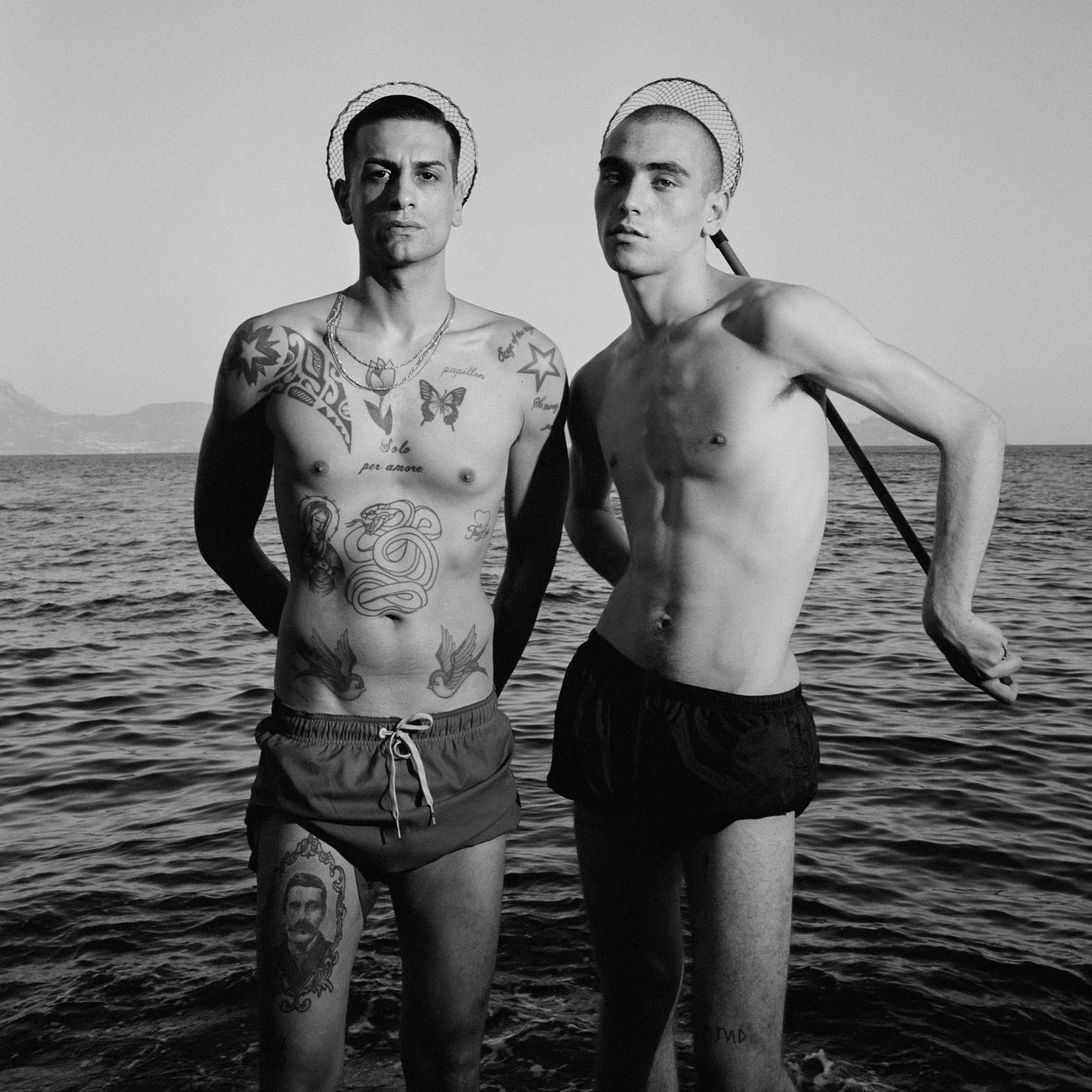

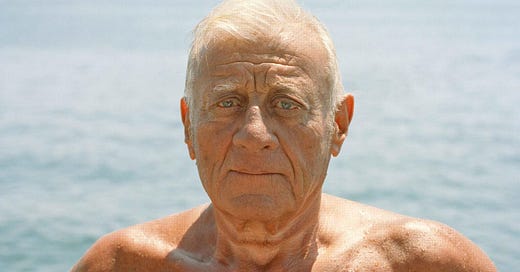

Napoli has become an aesthetic—its essence reframed into carefully curated glimpses: a man basking on the harbor, sun-drenched laundry flapping in the breeze, women with dramatic tattoos and lip liner. It’s a fashion photographer’s dreamland, and for many, that’s all it ever was. This representation of the city is oddly cohesive, don’t you think? It’s like all there ever is in Napoli is poetic moments of relaxation, carried out by people who look exactly like you pictured them in your head. Exaggerated gestures, overt faces, sun-dried skin, and a carefree attitude.

Let’s go over the process that one goes through when reading the news: you mix sources, and processes with the tools you have; if good enough, you might think you got a full overview of what’s happening. Is that really the case? We are in the POV era, and you can constantly see what other people see (and think) about a certain situation at hand. It opens you up to new ways of seeing and it wasn’t like this before Social Media came into the picture. What you see on Instagram about Napoli is a set of POVs, very flat and narrow, all looking like the one that you saw just before.

The year is 2021, I am sure you or a friend who visited have a video of bed covers hung between houses in Naples, gently moved by a light breeze. I know I have it. That’s when I started taking notice of this feeling of discomfort that lay around the corner.

Were the photographs by Brett Llyod so beautiful you wished to join in? He, Sam Youkilis, and others3 seemed to define the global outlook of Napoli. I discussed with a friend how, if our Ministry Of Tourism hired Lloyd, he would have made the same exact pictures. I disagree. I think that these pictures would have easily angered some people, mostly for their fetishization of certain activities and certain features. There comes a point when you ask yourself: why is the stereotype such a convenient mask?

I would say that stereotypes simplify complexity, making it easier for outsiders to consume and commodify what they see. For outsiders seeking beauty in simplicity, Napoli’s grit and struggle are sanitized into a digestible fantasy. This process involves a flattening of reality first, and an exoticization of resistance second. Outsiders focus on aesthetics (the sunlit harbor, tattooed women) while ignoring systemic issues like unemployment or inequality. Everyday acts of living -like basking in the sun at the harbor- become framed as “simple life” or a rejection of modernity. This echoes colonial tropes that romanticized the “noble savage” while ignoring the systems that created their circumstances. In a globalized world, this is a slippery slope. In a globalized world with Social media, an even slipperier one.

Why is the stereotype such a convenient mask?

For those seeking to profit, stereotypes that point to Napoli’s “gritty charm” serve as tools to:

Simplify the Narrative: It’s easier to sell a story about Napoli’s “slow life” than to grapple with the realities of systemic neglect.

Control the Narrative: Stereotypes allow outsiders to frame the city in ways that align with their interests, whether it’s selling magazines, tourism, or high-fashion campaigns.

Appeal to Nostalgia: Many consumers yearn for “simpler” times or places. Napoli, with its layered history and contradictions, becomes a blank canvas for those desires.

Orientalism and Napoli: Props on the loose

I want to talk about the process of Othering, and I want to do so by banging my head against the walls of institutional knowledge in liberal arts academies. I am talking about Orientalism, by Edward Said. He described Orientalism as the process by which Western societies romanticize, exoticize, and objectify the “Other.” It creates a fantasy of the foreign that serves the interests of the powerful, reducing real people and places to props and symbols. Replace “the Orient” with Napoli, and the parallels are striking. Napoli’s rise to fashion hotspot is less about the city’s true complexity and more about a carefully cultivated fiction. When Brett Lloyd photographs Neapolitans lounging on the waterfront or Sam Youkilis captures the grit and glamour of urban life, their lenses aren’t neutral. These images, for all their beauty, are still curated—driven by external desires and narratives that flatten the rich, messy reality of Naples into something digestible and sellable. The images’ subjects become emblematic, but not of themselves. Instead, they’re symbols of a “simple” life, stripped of context and commodified for audiences who yearn for the illusion of escape.

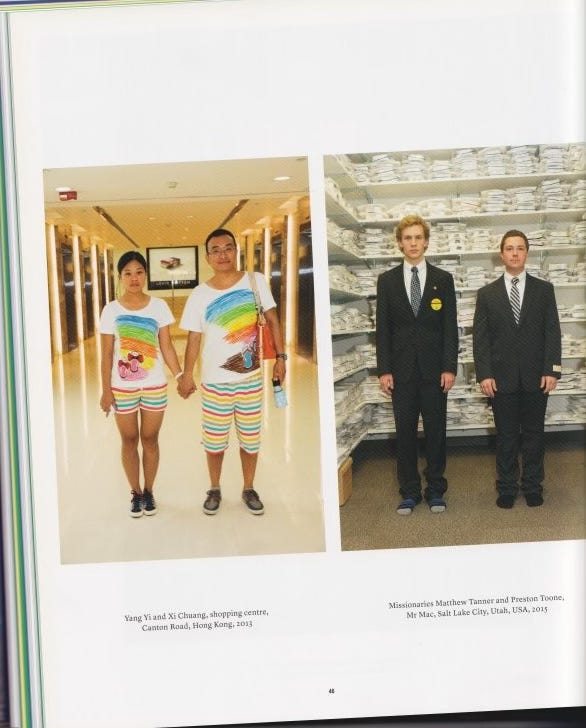

I was researching photography practices that worked this dynamic within their lenses, practices that entered the mainstream with it, and I couldn’t find a proper replica of what I described just now. I could find, however, one where the photographer is an insider. Enter: Martin Parr.

Parallels to Martin Parr’s Work

I’m really out of touch with any discourse that has happened around his work, beyond the classic voyeurism accusations, so I will write what I see and what I can grasp by reading about him and his work. I avoided critiques to fully experience my feelings about the photos and make up my mind without more biases. Feel free to enlighten me in the comments.

Martin Parr4, a British photographer, captures the working class in England with a distinctive blend of satire and affection. As an insider, Parr’s work complicates the idea of fetishization I was describing above. He is both a participant and an observer of the culture he frames. While exaggerated or ironic, his photos are rooted in a deep understanding of the social and cultural milieu. This insider status gives him a license to portray his subjects with nuances that outsiders often lack. I chose to write about his work because I could see how it could be perceived as just a fetishization of his subjects. I don’t think it is. It looks and feels more related to the absurdity of the human experience, rather than an attempt at packaging and romanticizing characters for external consumption.

In contrast, photographers like Brett Lloyd or Sam Youkilis, engage with Napoli from an outsider’s perspective. They often lack the cultural intimacy needed to understand the nuances of what they capture. As a result, their work risks veering into Orientalism, where Napoli’s working-class life is aestheticized for its “otherness,” not its humanity. Neapolitanism.

Now, no thoughts, just a bunch of quotes from Brett Llyod:

AnOther Magazine Interview: In a 2022 interview, Lloyd recounts his first encounter with Naples in 2010: "I was just mesmerized by it... I was just like, what the fuck is this place?" AnOther Magazine

Document Journal Feature: Lloyd describes his project Napoli Napoli Napoli as capturing:"...the more tranquil subset of Neapolitan life, an escape from the harsh realities of living in a crowded, working-class city." Document Journal

Office Magazine Article: Lloyd refers to his book as: "...his official love letter to the city, with the book Napoli Napoli Napoli, detailing visually the experience of a day from dawn til dusk in Naples." Office Magazine

Man...the whole city is working-class…2008 hit us like a train…

Jokes aside, I would love to hear his thoughts on such matters as representation and commodification. I think he was one of the major players when it came to defining Napoli’s current visual identity. Let’s see if I can make it happen.

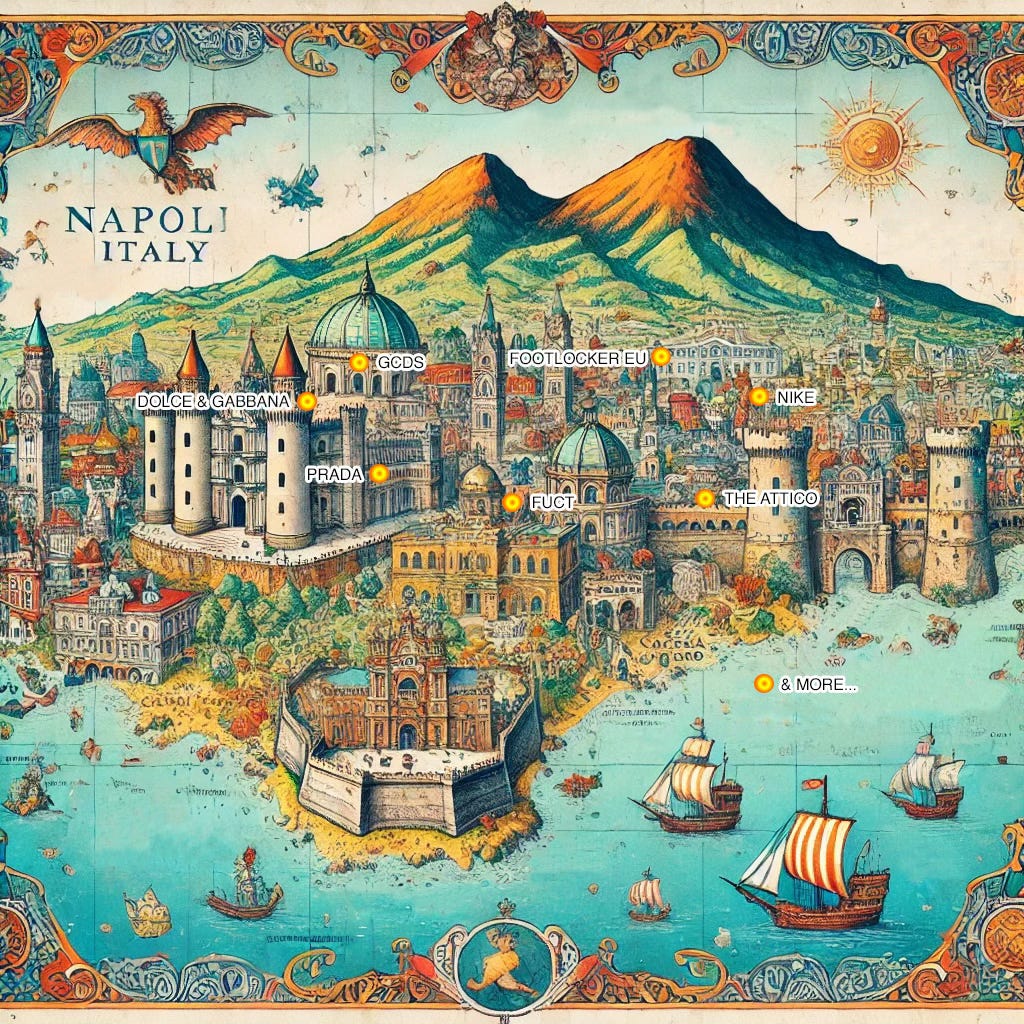

The Rise: Fashion Moments in Napoli

Napoli’s emergence as a fashion hotspot didn’t happen overnight. High-fashion brands have flocked to its crumbling facades and vibrant streets in search of authenticity for a long time—or at least the kind of authenticity that photographs well. Here are some key moments that I can mention without putting my ghost-writing work in fashion on the line:

Dolce & Gabbana5 hosted an Alta Moda show in Napoli, in 2016. Models strutted past locals who became part of the mise-en-scène, whether they liked it or not.

Here’s a map of brands that featured Napoli in their work during these years.

And...that’s it. Look online, there are plenty of instances. Supposedly a hymn to Italian beauty, focusing on “raw” and “undistilled” imagery that screams, “We’re keeping it real.”

What “real” is it’s still up for discussion. Each of these moments trades on the same premise: Napoli is beautiful in its chaos, its rough edges making it the perfect foil for sleek, expensive fashion. But this aestheticization doesn’t benefit the people of Napoli—it merely packages their lives for outsiders to consume. Going back to the Orientalism bit, think of any Kardashian crossover with Italy. From the Kim VS Kourtney feud, threaded over a Dolce and Gabbana partnership6, to their holidays in Capri. Friends of friends put me on some jokes that run in the island's kitchens. Americans from all over come to Capri, Positano, and such and ask for Sicilian food, clearly unable to tell the difference. The South is a unified experience for foreigners.

My mind goes to the movie “Beirut”, which had some backlash when it was released. You would think “Beirut” has to take place in Beirut, but it was filmed exclusively in Tangier, Morocco. “The Orient” becomes a singular place, any spot interchangeable for another, and what about its people? The people are reduced to a set of traits and temperaments.

Remember: “Pizza, Mafia!”. What you would hear the most about Neapolitans a few years ago was: they steal, they are criminals, poor and uneducated people, gullible, violent, and lazy. The lazy bit stuck to today’s version, in a more gentle light. They are bathing in the sun! They never work, they’re so appreciative of life, so unaware of its complexities. Maybe it’s not gentle, just diminishing. But hey, it makes the whole so easy to pin, it’s brandable.

Is this inherently bad? Is it good when people from the city do it and bad when outsiders shape the brand for them to adhere to? While looking for answers, let’s look at two examples: Cairo, during the 19th century, and Bali in an “Eat, Pray, Love” aftermath.

Cairo and the Orientalist Gaze

Western artists, writers, and travelers like Edward Lane and Eugène Delacroix often depicted Cairo as a city frozen in an exotic and timeless past. The focus was on bazaars, minarets, and veiled women, all framed through the lens of mystique and decadence.

Cairo was often presented as interchangeable with any “Eastern” city, collapsing distinctions between Egypt, The Levant, and North Africa into a singular “Orient”. The people of Cairo were portrayed as indolent, sensuous, and steeped in ancient tradition, all while ignoring the city’s changes under leaders like Muhammad Ali.

These depictions created a marketable myth that still influences tourism and media portrayals of Cairo, reducing it to pyramids, camels, and bazaars.

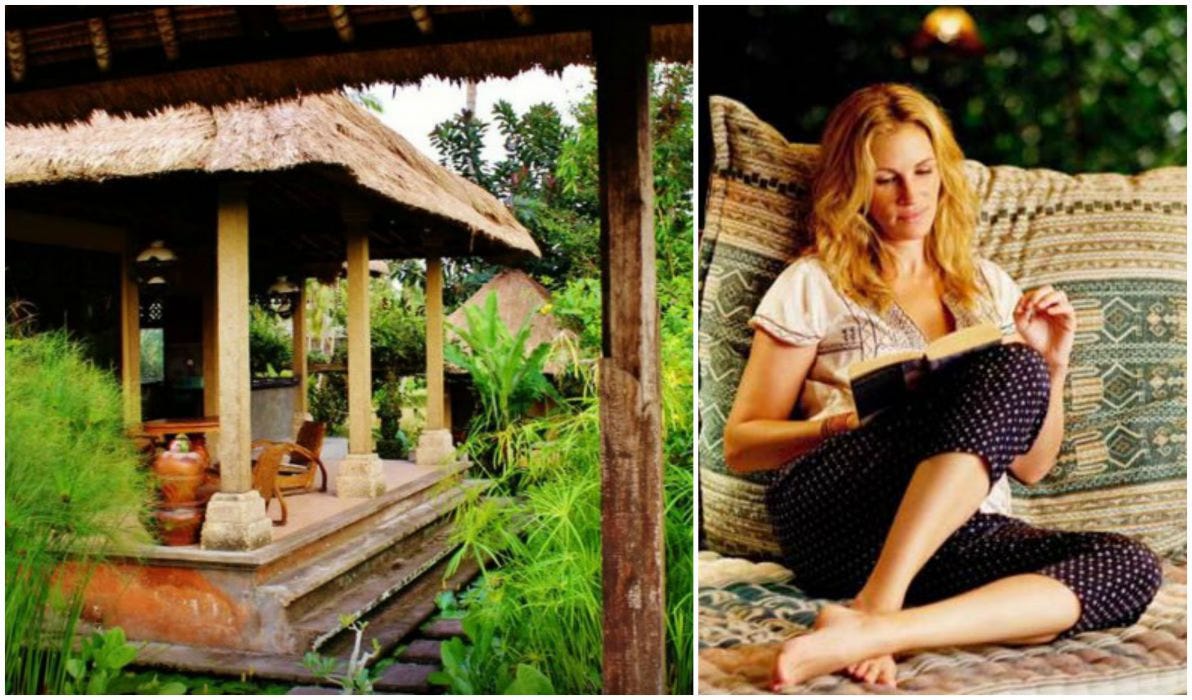

Bali as a Spiritual Retreat for the West

In recent decades, Bali has become a symbol of spiritual and physical escape for wealthy Western tourists. The global yoga and wellness industries, as well as influencers, have turned Bali into a commodified paradise. Bali’s identity as a unique cultural hub has been diluted into a generic image of palm trees, beaches, and yoga retreats. It’s often interchangeable with other tropical destinations like Thailand or Costa Rica.

Balinese people are often portrayed as perpetually smiling, carefree, and deeply spiritual, ignoring the socioeconomic realities and environmental strain caused by mass tourism.

The “Eat, Pray, Love” phenomenon cemented Bali as a destination for self-discovery, but this narrative primarily serves outsiders, erasing the complex realities of Balinese life and reducing it to a backdrop for personal transformation.

While trying to think of a place that branded itself and made it benefit the people within it, I could come up with America. You know, the old “I love America” statement but it’s North America, with 52 states so different from each other. America is a unified reality for foreigners. America is 32.5 times bigger than Italy. We have regional dialects that make it impossible for you to understand what’s being said in another region, I can’t fathom another State.

So, people branding from the outside = bad, people from the inside doing it= good?

I believe it is, like in almost every case, a question of nuances. It is true that when outsiders impose a narrative, it can feel reductive or exploitative, especially if it reduces complexity to easily consumable stereotypes. However, outsiders can also serve as mirrors, reflecting beauty in the every day that insiders may have normalized or dismissed.

Thus, the issue isn’t so much about who tells the story but about the intent and depth of their storytelling. Are they seeking to understand and reflect, or are they simplifying for profit and appeal?

The Fall: From Idealized to Irrelevant

What happens when a place becomes a brand? Napoli, as it is currently idealized, risks falling victim to the same fate as all overexposed trends. When a city’s image is reduced to a series of profitable codes—“sun-drenched simplicity,” “unfiltered grit,” “traditional but chic”—the essence of the place is hollowed out. Here’s how it unravels:

Oversaturation: The more a place is featured in campaigns and social media, the more it becomes predictable. Novelty fades, and the “magic” gives way to indifference.

Cultural Exploitation Fatigue: Locals grow weary of being props in someone else’s story. Authenticity—the very thing that made Napoli desirable—is lost when it becomes over-performed.

Economic Displacement: Tourism and fashion campaigns drive up costs for locals while failing to invest in real infrastructure or opportunities. This creates resentment and, eventually, backlash.

A brilliant example of a city’s branding through social media can be found in the New York Times article about Bologna: “My Beloved Italian City Has Turned Into Tourist Hell. Must We Really Travel Like This?” The writer, Ilaria Maria Sala, was born in Bologna and wrote about the complex dynamics of a city that changed radically with overtourism. She observes that budget airlines, short-term rentals, and social media have significantly increased tourist numbers, leading to higher rents and the displacement of local students to peripheral towns. Sala laments that Bologna is becoming a typical tourist city, where main roads are overcrowded, and the authentic charm is diminishing. Bologna has one historical food that is recognized worldwide and it’s mortadella. Americans call it “baloney”, which makes sense when you read the name of the city in an American accent. This culinary product became tied to the city’s image through marketing, cookbooks, and social media. It’s almost a simulacra for the city itself, according to Ilaria Maria Sala, and people are tired.

Bologna, through the lens of outsiders, risks becoming little more than an idea—its essence obscured by the very images meant to celebrate it.

Napoli’s fall feels inevitable then, the warning signs are all here already. I venture to say it’s here already. As the city becomes more of an aesthetic and less of a lived reality, its allure fades away. The trend-chasers will move on to the next “authentic” spot, leaving Naples with little to show for its time in the spotlight.

What Comes Next?

I know what I should say. We should not allow people from the outside to define Napoli for us, we should resist the narrative. Problem is, it’s too alluring. You’re talking about people who felt like second-class citizens until a few years ago, and in some ways still are. Now that everyone has jumped in on the wagon, we cannot derail it. Like when a guy from the university called me “Margherita” and asked if I could make a pizza, my feelings conflicted. On one hand, you have to punch the said guy, on the other hand, the consequences of said punch would leave you the most impacted. I think it is easier to see people from Napoli play the part outsiders are invested in, rather than outsiders investing in unraveling the mess beneath the surface.

It’s a power play now. We got their attention, it’s already fading away and we should think about what comes next. Ugly truth or beautiful pictures? We can do both or neither, we can even do something else entirely… just saying.

You can hear in this video: Matteo Salvini, our current Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Infrastructure and Transport, , singing a song that says “Senti che puzza, scappano anche i cani, stanno arrivando i Napoletani” // "Smell that stench, even the dogs are running away, the Neapolitans are coming.". The video was recorded on the 13th of June, 2009. For more dirt on these populist narratives look up “Lega Nord” and its rise to power in recent years.

Pino Daniele's 1977 album Terra Mia is a great listening suggestion, to best grasp the positive cultural moment. It combined traditional Neapolitan melodies with modern sounds and social commentary, becoming an anthem for a generation that sought to celebrate Naples’ identity amidst adversity.

A quote from Robbie McIntosh’s website: Although Robbie sees these regulars, regularly – he is cautious not to get too chummy. He says: “Of course, I’m close with them but I also believe every good photographer should never be too involved. Being a friendly, curious dancing ghost is much better.” His gaze is focused not only on the city center and its beaches, but also on the suburbs such as Scampia, Licola, Castel Volturno, and the entire vast Campania Hinterland. I found it interesting, since the distance it speaks of is what I guess comes to the forefront when analyzing not only his photos, but that of many others. There is an eye for the shot, not one for the humanity within it. As above, so below, I would love to hear your opinions on this!

On why the “Mandolin” skirt has me in tears. The modern mandolin, with its signature bowl-shaped back and eight strings (in four courses), was perfected in Naples in the 18th century. The Neapolitan mandolin, designed by luthiers like the Vinaccia family, became the standard form. When people mock Italians, abroad or in Northern Italy, “Pizza, Mafia” can also become “Pizza, Mafia, Mandolino”.

Here is a summary on the feud. Over to Kardashian Kolloquium for “A Kompendium of notes/reflections/theories”. Cheers!

Ok. It took me ages to finally read this piece, as it's been sitting in my notes app for months. I wish I read this sooner. Fantastic analysis, critical but objective. You wrote with candor and purpose. Thoroughly enjoyed reading this! Great work.